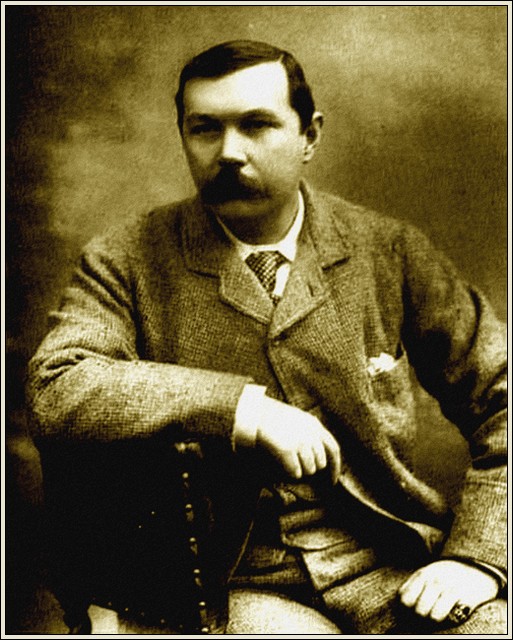

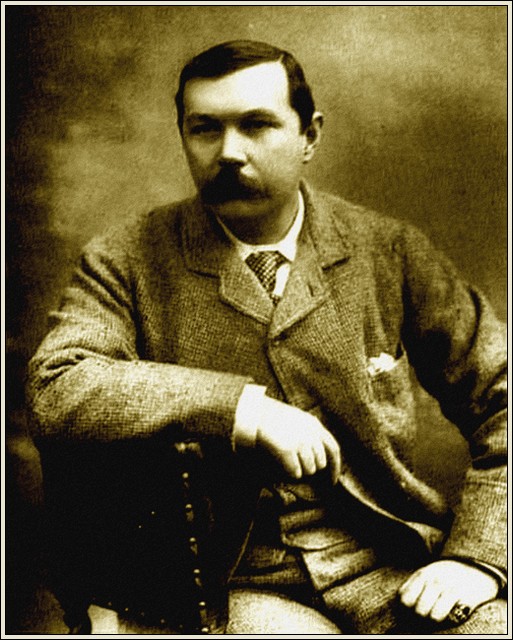

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, had a long association with Switzerland, even making a claim that he was “the first to introduce [skiing] for long journeys into Switzerland”. On a trip to Switzerland his wife contracted tuberculosis and the family decided in 1893 to move to Davos (in what we call Graubünden but which the French call the Grisons) where the crisp, clean mountain air and the clinics were famous for their impact on the well-being of patients with respiratory problems. Interestingly Conan Doyle was himself an MD, having studied medicine in Edinburgh. To while away the time Conan Doyle, a keen sportsman, tried many diversions. In his autobiography, “Memories and Adventures” (1924, London) he recounts:

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, had a long association with Switzerland, even making a claim that he was “the first to introduce [skiing] for long journeys into Switzerland”. On a trip to Switzerland his wife contracted tuberculosis and the family decided in 1893 to move to Davos (in what we call Graubünden but which the French call the Grisons) where the crisp, clean mountain air and the clinics were famous for their impact on the well-being of patients with respiratory problems. Interestingly Conan Doyle was himself an MD, having studied medicine in Edinburgh. To while away the time Conan Doyle, a keen sportsman, tried many diversions. In his autobiography, “Memories and Adventures” (1924, London) he recounts:

“As there were no particular social distractions at Davos, and as our life was bounded by the snow and fir which girt us in, I was able to devote myself to doing a good deal of work and also to taking up with some energy the winter sports for which the place is famous.”

He continues:

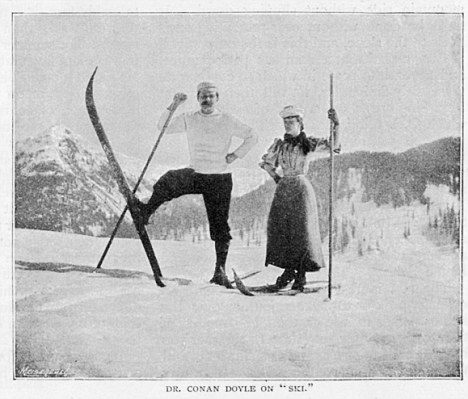

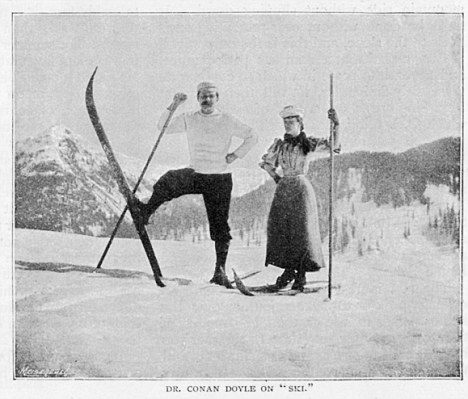

“There is one form of sport in which I have, I think, been able to do some practical good, for I can claim to have been the first to introduce skis into the Grisons division of Switzerland, or at least to demonstrate their practical utility as a means of getting across in winter from one valley to another. It was in 1894 that I read Nansen’s account of his crossing of Greenland, and thus became interested in the subject of ski-ing. It chanced that I was compelled to spend that winter in the Davos valley, and I spoke about the matter to Tobias Branger, a sporting tradesman in the village, who in turn interested his brother. We sent for skis from Norway, and for some weeks afforded innocent amusement to a large number of people who watched our awkward movements and complex tumbles. The Brangers made much better progress than I. At the end of a month or so we felt that we were getting more expert, and determined to climb the Jacobshorn, a considerable hill just opposite the Davos Hotel. We had to carry our unwieldy skis upon our backs until we had passed the fir trees which line its slopes, but once in the open we made splendid progress, and had the satisfaction of seeing the flags in the village dipped in our honour when we reached the summit. But it was only in returning that we got the full flavour of ski-ing. In ascending you shuffle up by long zigzags, the only advantage of your footgear being that it is carrying you over snow which would engulf you without it. But coming back you simply turn your long toes and let yourself go, gliding delightfully over the gentle slopes, flying down the steeper ones, taking an occasional cropper, but getting as near to flying as any earth-bound man can. In that glorious air it is a delightful experience.

“Encouraged by our success with the Jacobshorn, we determined to show the utility of our accomplishment by opening up communications with Arosa, which lies in a parallel valley and can only be reached in winter by a very long and roundabout railway journey. To do this we had to cross a high pass, and then drop down on the other side. It was a most interesting journey, and we felt all the pride of pioneers as we arrived in Arosa.”

It was an interesting early example of back-country skiing, and I must admit that I have not attempted to make the journey from Davos to Arosa, by skis. One to add to the list.

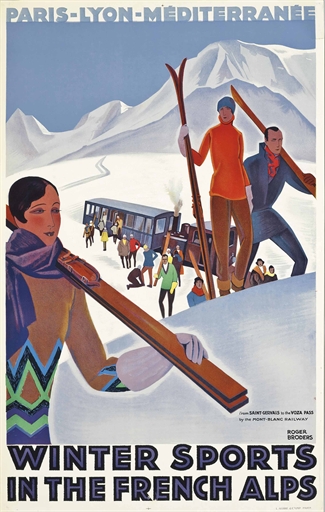

Conan Doyle wrote prolifically, and no doubt engendered interest in the English public (or at least a section of it) through his enthusiastic reports on “ski-running”, as he often called it. In an article in the Strand Magazine in 1894 he opined “Ski-ing opens up a field of sport which is, I think unique. I am convicted that the time will come when hundreds of Englishmen will come to Switzerland for the ski-ing season in March and April”. He described the sport as one where “You have to shuffle along the level, to zigzag, or move crab fashion, up the hills, to slide down without losing your balance, and above all to turn with facility.” Whenever I ski the Jakobshorn, I can’t help but think of Conan Doyle energetically moving crab fashion in his tweeds and eight-foot long skis, “occasionally taking a cropper”.

However Conan Doyle’s most famous association with Switzerland is entirely fictional.

Conan Doyle was frustrated that most of his writing received little attention, except for his Sherlock Holmes stories. As he wrote in his memoirs:

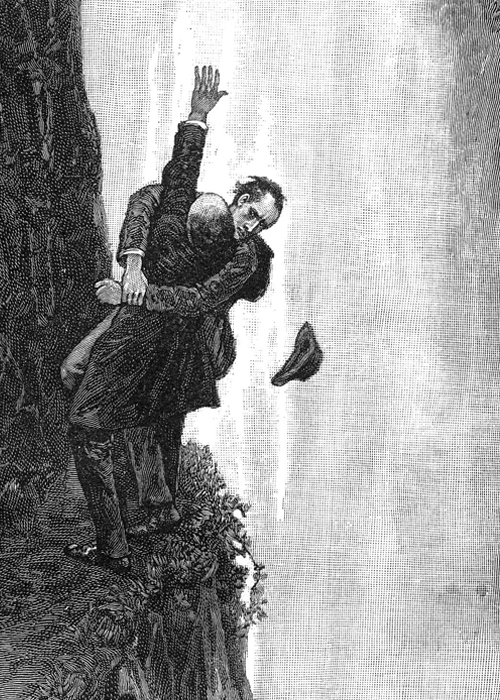

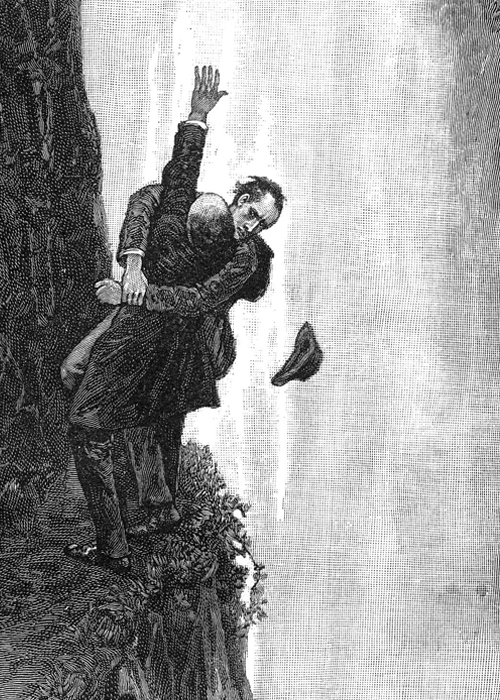

“It was still the Sherlock Holmes stories for which the public clamoured, and these from time to time I endeavoured to supply. At last, after I had done two series of them I saw that I was in danger of having my hand forced, and of being entirely identified with what I regarded as a lower stratum of literary achievement. Therefore as a sign of my resolution I determined to end the life of my hero. The idea was in my mind when I went with my wife for a short holiday in Switzerland, in the course of which we saw there the wonderful falls of Reichenbach, a terrible place, and one that I thought would make a worthy tomb for poor Sherlock, even if I buried my banking account along with him.”

So Conan Doyle placed the demise of his most famous invention, Sherlock Holmes, at a waterfall just outside the resort of Meiringen in his story, “The Final Problem”, published in The Strand Magazine in December 1893. A small museum, below the church near the station in Meiringen, commemorates the association of Conan Doyle with the area. In the story Holmes spends his last night at the Park Hotel Du Savage (renamed by Conan Doyle as the Englischer Hof) before visiting the Reichenbach Falls, where both Holmes and Moriaty meet their fate. At the fictional spot where this happens a plaque in English, German, and French reads “At this fearful place, Sherlock Holmes vanquished Professor Moriarty, on 4 May 1891.”

According to his memoirs Conan Doyle also lived in Maloja in Graubünden for a time and in Caux, above Lake Geneva, reached by funicular railway from Montreux.