Switzerland is fortunate to have some of the very best ski resorts in the world, and Zermatt and Verbier are amongst the very best. But how do they compare?

Location

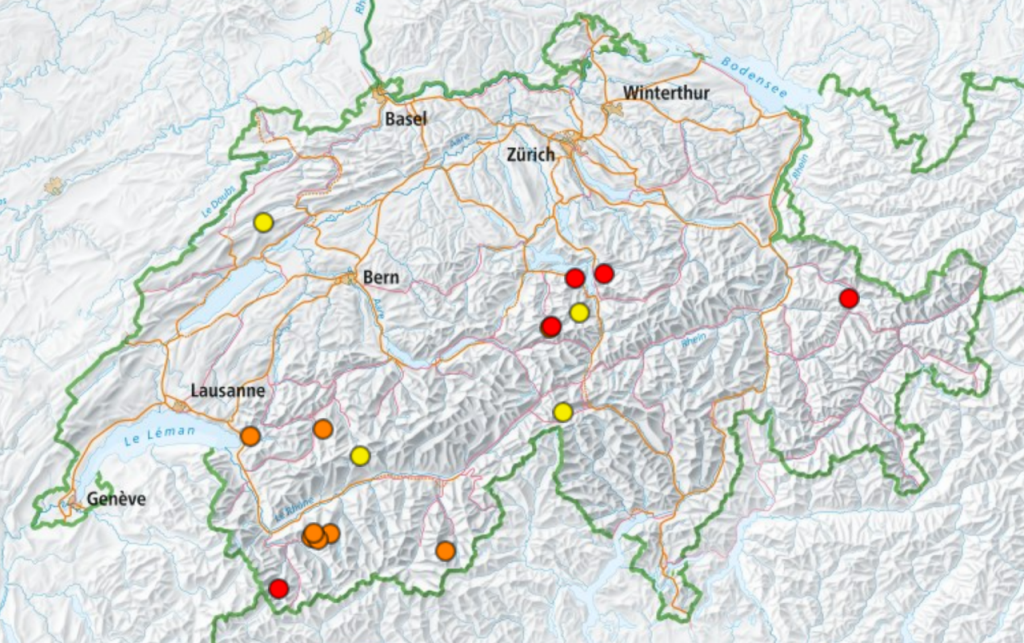

Both resorts are in the Pennine Alps in the Swiss canton of Valais, and both are high, particularly Zermatt. The most obvious difference between them is that Zermatt is in the part of Switzerland where a uniquely Swiss form of German is spoken, whereas Verbier is French-speaking. Verbier rests on a sunny plateau above the valley of Bagnes, whereas Zermatt lies right at the head of a long steep valley. The nearest international airport to Verbier is Geneva, whilst Zermatt is equally served by Geneva and Zurich airports.

Both relatively convenient for international visitors.

Pistes

Zermatt has 360km of piste spread over four highly integrated ski areas in Switzerland and two across the border in Italy. Although Verbier is part of the extensive Four Valleys, with 412km of piste, the valleys are less well connected than Zermatt, and you will probably not get round to visiting some of the more remote slopes beyond Siviez. Honours even.

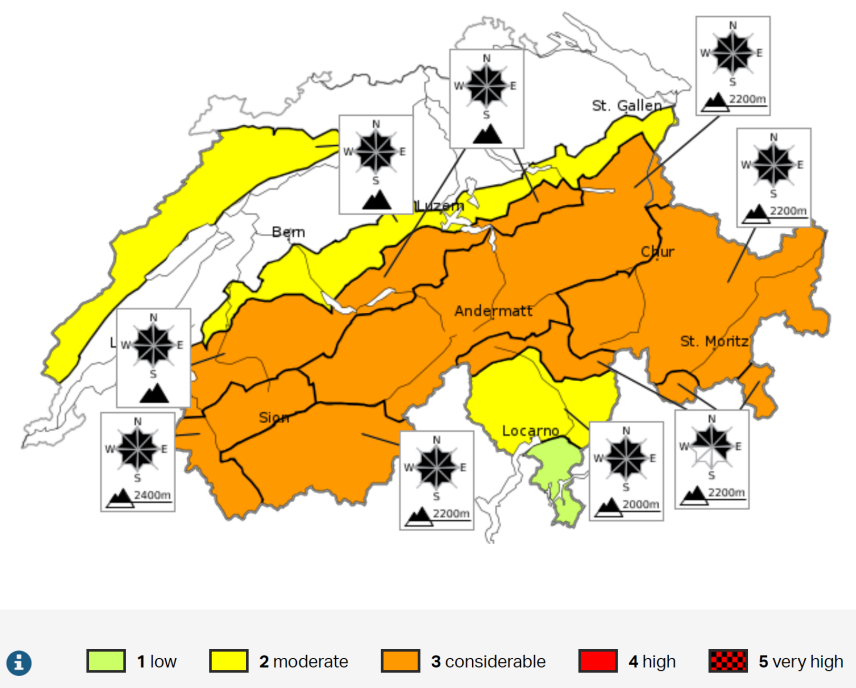

Season

Pretty much nowhere in the world can beat Zermatt for year-round skiing. Granted that summer skiing is something of a novelty, Zermatt nonetheless offers extensive glacier skiing from the beginning of November right through to the end of May, with the full extent of the resort available from the beginning of December until the end of April.

Verbier normally opens up one piste in November, and the resort progressively opens up in the following weeks. Normally the season finishes in mid-April.

For early and late season skiing, nothing beats Zermatt, but it can get very cold in the heart of the winter.

Zermatt for early and late season, Verbier edges it for mid-season.

Beginners

Neither resort is especially good for beginners, but Verbier does have a nursery area in the village. Unless you are coming with a mixed ability party which includes experts, or you just want to party, neither resort is recommended for beginners. You pay a premium in these resorts because of challenging slopes a beginner will never get to experience.

Beginners should look elsewhere but, if you had to choose, Verbier is better.

Intermediates

I think both resorts are excellent for intermediates. If you come for a week or two you will never want for more variety or challenge, or for nice cruisy runs when you have a hangover to shake off.

Even Stevens.

Expert

Both resorts have good skiing for experts, but if you want to stick to ungroomed trails and challenging lift-served off-piste, Verbier has more to offer. For back-country ski touring they both make excellent bases, and both lie on the famous Haute Route (Verbier only on a variation of the classic route).

Verbier is my recommendation.

Apres-ski

Apres-ski in Switzerland is generally more subdued than in other Alpine nations, but Verbier and Zermatt are exceptions to the rule. They both rock, but I prefer…

Zermatt.

Mountain Restaurants

Both resorts have a mix of cafeteria restaurants with sunny balconies and charming restaurants in the mountains. However Zermatt is something of an epicurean’s delight with some of the most outstanding mountain restaurants in the world. Not really a contest if you want haute cuisine for lunch. But it comes at a price. In the resorts themselves there is a wide range of options from street food to Michelin-starred restaurants.

The Blue Ribbon goes to Zermatt.

Resort Charm

Lying beneath the Matterhorn, nowhere quite matches Zermatt for chocolate box pretty. It is car-free, although not traffic-free as the electric taxis and service vehicles mean some streets are quite busy. It has a fabulous Alpine tradition stretching back many centuries, and was well-established as a tourist destination by the middle of the 19th Century. Verbier, conversely, is largely a post-war resort, but it’s ubiquitous chalet-style architecture is not without its charm.

Zermatt has it all.

Access – Car

You can’t drive to Zermatt, you have to pay to leave your car in a car park in a neighbouring town and take a train for the last section. Verbier does have full car access, but you generally need to pay for parking unless it comes with your chalet. There is free parking at the bottom station of the gondola that passes through Verbier at Le Châble .

Assuming you are driving from the Lake Geneva Region, it will take you about 3 hours to get to Täsch, the end of the road, and then 10 minutes by train to Zermatt.

Verbier is one of the easiest resorts to get to from Geneva, 2 hours of mainly motorway to Le Châble, and about another 10 minutes drive from there up to Verbier.

Verbier is the easier to get to from almost anywhere.

Access – Train

Zermatt is very easy to get to from either Zurich or Geneva airport by train – both airports actually have railway stations in the airports themselves and you can get to the resort with as few as one change (in Visp). Journey time from Zurich Airport is just under 4 hours, from Geneva Airport just over 4 hours.

For Verbier, Le Châble is just over 2 hours from Geneva Airport with a change at Martigny. From Le Châble you can either take the gondola or the local bus service into Verbier.

The train to Zermatt is a joy even if the journey time is longer.

Cost

You would struggle to find two more expensive resorts in the Alps than Zermatt and Verbier, but it is possible to enjoy them both on a budget. First of all the lift passes are probably cheaper than in comparable French and Austrian resorts – a typical day pass for Verbier is SFr 71, and SFr 92 for Zermatt, and longer stays are substantially cheper per diem. For accommodation, there are affordable hostels and basic accommodation in Zermatt itself and in Le Châble for Verbier. You can also ski the slopes of Zermatt from Cervinia in Italy. Although eating and drinking out is expensive in Switzerland, supermarket prices for alcohol and, to a lesser extent, food staples are not expensive by European standards so self-catering will certainly make your francs go further.

Neither resort is cheap, but there aren’t many resorts that come close to being this good.